Scotland helped educate a medical pioneer who made history in more ways than one.

“When I was a boy, I was told that when I began a story, to begin at the beginning and continue to the end.” That’s good advice for any writer, but for anyone attempting to follow the life story of Dr James Barry, the man who said it, there are two particular problems.

First: a singular revelation following Barry’s death 150 years ago, has tended to completely overshadow his acclaimed – and occasionally controversial – medical career, during which time he instigated radical reforms to battlefield medicine, promoted good hygiene and healthy mixed diets, and helped saved thousands of lives.

Incidentally, that includes, in around 1855, seriously berating the future “Lady of the Lamp” Florence Nightingale while studying the appalling death rates in her hospital in Scutari, near modern Istanbul. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, she later described him as “the most hardened creature I ever met”.

Second: as author Rachel Holmes points out in her 2002 biography, Scanty Particulars: The Life of Dr James Barry, it’s “a vexing prospect for any biographer to attempt to write about a subject who appears to have no childhood.”

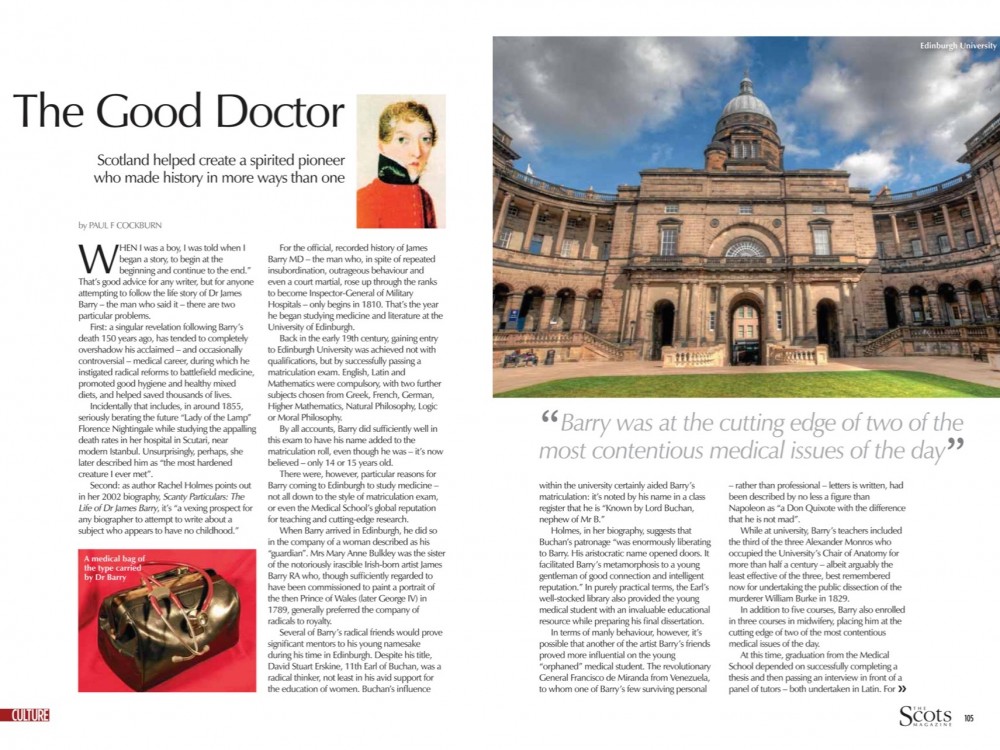

For the official, recorded history of James Barry MD – the man who, in spite of repeated insubordination, outrageous behaviour and even a court martial, rose up through the ranks to become Inspector-General of Military Hospitals – only begins in 1810, when he began studying medicine and literature at the University of Edinburgh.

Back in the early 19th century, gaining entry to Edinburgh University was achieved not with qualifications, but by successfully passing a Matriculation exam. English, Latin and Mathematics were compulsory two further subjects from Greek, French, German, Higher Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, Logic or Moral Philosophy.

By all accounts, Barry did sufficiently well in this exam to have his name added to the matriculation roll, even though he was – it’s now believed – only 14 or 15 years old at the time. There were, however, particular reasons for Barry coming to Edinburgh to study medicine, and not all were down to the style of matriculation exam or the Medical School’s global reputation for teaching and cutting-edge research.

When Barry arrived in Edinburgh, he did so in the company of a woman described as his “guardian”. Mrs Mary Anne Bulkley was the sister of the notoriously irascible Irish-born artist James Barry RA who, though sufficiently regarded to have been commissioned to paint a portrait of the then-Prince of Wales (later George IV) in 1789, generally preferred the company of radicals to royalty.

Several of Barry’s radical friends would prove significant mentors to his young namesake during his time in Edinburgh. Despite his title, David Stuart Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan, was a radical thinker, not least in his avid support for the education of women. Buchan’s influence within the university certainly aided Murray’s matriculation: it’s noted by Barry’s name in a class register that he is “Known by Lord Buchan, nephew of Mr B.”

Holmes, in her biography, suggests that Buchan’s patronage “was enormously liberating to Barry. His aristocratic name opened doors. It facilitated Barry’s metamorphosis to a young gentleman of good connection and intelligent reputation.” In purely practical terms, the Earl’s well-stocked library also provided the young medical student with an invaluable educational resource while preparing his final dissertation.

In terms of manly behaviour, however it’s possible that another of the artist Barry’s friends proved more influential on the young “orphaned” medical student. The revolutionary General Francesca Miranda from Venezuela, to whom one of Barry’s few surviving personal (rather than professional) letters is written, had been described by no less than Napoleon as “a Don Quixote with the difference that he is not mad”.

While at University, Barry’s teachers included the third of the three Alexander Monros who occupied the University’s Chair of Anatomy for more than half a century – albeit, arguably the least effective of the three, best remembered now for undertaking the public dissection of the murderer William Burke in 1829. In addition to five courses, Barry also enrolled in three courses in midwifery, placing him at the cutting edge of two of the most contentious medical issues of the day.

At this time, graduation from the Medical School depended on successfully completing a thesis and then passing an interview in front of a panel of tutors – both undertaken in Latin. For any student the challenge wasn’t simply to prove their medical competency; the test was as much about showing they were worthy to become a graduate of the Edinburgh school and to enter what was viewed as a highly privileged profession.

Barry’s first request to enter for the degree examination was refused, officially on the grounds of his “extreme youth”. Luckily, his mentor Buchan pointed out to the authorities that the university’s regulations didn’t specifically state a minimum age for degree candidates, and so – in the summer of 1812 – Barry presented himself for examination and passed with flying colours.

History was made that day, but it would be 54 years before anyone realised, after his death in London during the dysentery-ridden heatwave of 1865.

For, following his funeral, Sophia Bishop, the charwoman who had been asked to prepare the body, insisted that Dr James Barry had, in fact, been “a whole woman”: a woman who had unknowingly become the first of her gender to graduate as a doctor in Britain, and who had successfully breached the barricades of not just one but two male professions – medicine and military.

So who was the young woman that became Dr James Barry? After nearly 150 years, determined detective work by retired urologist Dr Michael du Preez – who had heard tales of the doctor’s work as a boy growing up in Cape Town – helped confirm that the young medical student wasn’t the artist Barry’s nephew – but in fact his young niece, Margaret Ann Bulkley, daughter of ill-fated master grocer Jeremiah Bulkley and his sister Mary Ann.

So why the lifelong “deception”? In the years following the revelation, numerous suggestions have been made: that Margaret Ann had fallen in love with a young medical doctor and so opted for the subterfuge in order to follow him. Or that she was what would now be termed “inter-sex”, and so not suitable marriage material.

du Preez, however, opts for the simpler case of her simply wanting to be a doctor. “I have not established any evidence that Dr Barry had an organic intersex disorder, such as hermaphroditism,” he insists. “It is my firm belief that Barry was a normal female. A cross dresser, yes, but not for any psychological hangup – rather, simple necessity.”

Holmes has suggested there were practical considerations, given that the young girl had been effectively disinherited by her father and profligate brother; if marriage was, for whatever reason, not an option, her uncle and his radical friends were clearly complicit in her “alternative career”.

Four years after Dr James Barry’s death, seven women successfully matriculated at the University of Edinburgh, the first British institution of higher education to accept women into its medical courses. While subsequent opposition ensured this “Edinburgh Seven” never graduated, their campaign proved a significant point in female emancipation, and women’s rights to be themselves – an opportunity lost to Margaret Ann Bulkley.

First published in the July 2015 issue of The Scots Magazine.