Fortune, alas, doesn’t always favour the bold.

There is absolutely no doubt that Angus-born James Tytler was the first person in Britain to ascend into the sky by balloon. The London Chronicle of 27 August 1784 reported: “The Balloon being filled at Comely Gardens [in Edinburgh], he seated himself in the basket and, the ropes being cut, he ascended very high and descended quite gradually on the road to Restalrig, about half a mile from the place where he rose, to the great Satisfaction of those Spectators who were present.”

While undoubtedly “the first person in Britain who has navigated the Air,” Tytler – later described by Robert Burns as a “poor devil in a skylight hat and hardly a shoe to his feet” – was soon forgotten when, less than a month later, a young Italian diplomat called Vincenzo Lunardi made a far more successful balloon ascent from the heart of London, in front of a crowd of some 150,000 people including the future George IV.

Indeed, it’s possible that, the following year, Tytler – by then living in the Debtor’s Sanctuary within the grounds of the Palace of Holyroodhouse – saw that same “daredevil aeronaut” welcomed by ecstatic crowds en route to a civic reception celebrating his first successful balloon flight across the Firth of Forth.

Arguably, though, Lunardi was always better suited to the role of aeronautical pioneer; not only was the young Italian well-read in the scientific literature of the day, but even the famed Edinburgh caricaturist John Kay had to admit that he cut a genuinely dashing and attractive figure. Tytler, in contrast, was an Edinburgh Aunt Sally, openly mocked by children in the street.

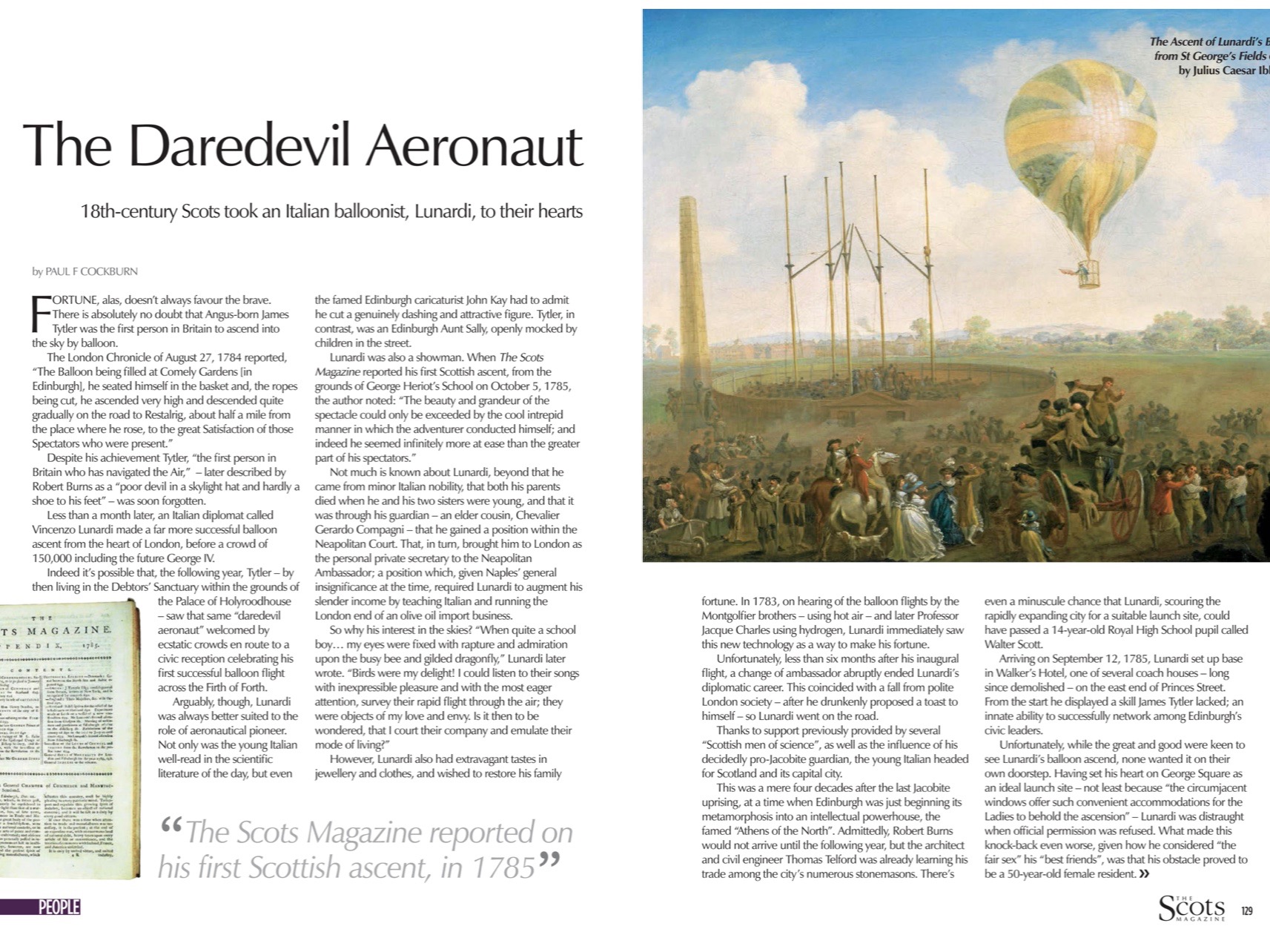

Also, Lunardi knew how to put on a show. When The Scots Magazine reported his first Scottish ascent, from the grounds of George Heriot’s School on 5 October 1785, the author noted: “The beauty and grandeur of the spectacle could only be exceeded by the cool intrepid manner in which the adventurer conducted himself; and indeed he seemed infinitely more at ease than the greater part of his spectators.”

Not much is known about Vincenzo Lunardi, beyond that he came from minor Italian nobility, that both his parents died when he and his two sisters were young, and that it was through his guardian – an elder cousin, Chevalier Gerardo Compagni – that he gained a position within the Neapolitan Court. That, in turn, brought him to London as the personal private secretary to the Neapolitan Ambassador; a position which, given Naples’ general insignificance at the time, required Lunardi to augment his slender income by teaching Italian and running the London-end of an olive oil import business.

So why his interest in the skies? “When quite a school boy … my eyes were fixed with rapture and admiration upon the busy bee and gilded dragon-fly,” Lunardi later wrote to Compagni. “Birds were my delight! I could listen to their songs with inexpressible pleasure and with the most eager attention, survey their rapid flight through the air; they were objects of my love and envy: is it then to be wondered, that I court their company and emulate their mode of living?”

However, Lunardi also had extravagant tastes in jewellery and clothes, and wished to restore his family fortune as quickly as possible. In 1783, on hearing of the early balloon flights by the Montgolfier brothers (using hot air) and later Professor Jacque Charles (using hydrogen), Lunardi immediately saw this new technology as a way to make his fortune.

Unfortunately, less than six months after his inaugural flight, a change of ambassador abruptly ended Lunardi’s diplomatic career; this coincided with a fall from polite London society, after drunkenly proposing a toast to himself. So Lunardi went on the road. Thanks to support previously provided by several “Scottish men of science”, as well as the influence of his decidedly pro-Jacobite guardian, the young Italian headed for Scotland and its capital city.

This was a mere four decades after the last Jacobite uprising, at a time when Edinburgh was just beginning its metamorphosis into an intellectual powerhouse, the famed “Athens of the North”. Admittedly, Robert Burns wouldn’t arrive until the following year, but the architect and civil engineer Thomas Telford was already learning his trade among the city’s numerous stone masons. There’s even a minuscule chance that Lunardi, scouring the rapidly expanding city for a suitable launch site, could have passed a 14-year-old Royal High School pupil called Walter Scott.

Arriving on 12 September 1785, Lunardi set up base in Walker’s Hotel, one of several coach houses – long since demolished – on the east end of Princes Street. From the start he displayed a skill James Tytler lacked; an innate ability to successfully network among Edinburgh’s civic leaders.

Unfortunately, while the great and good were keen to see Lunardi’s balloon ascend, none wanted it on their own doorstep. Having set his heart on George Square as an ideal launch site – not least because “the circumjacent windows offer such convenient accommodations for the Ladies to behold the ascension” – Lunardi was distraught when official permission was refused. What made this knock-back even worse was that, given how he considered “the Fair Sex” his “best friends”, his obstacle proved to be a 50-year-old female resident.

In general, though, Lunardi praised those Scottish ladies he met; and he could charm the men too. “A great number of gentlemen from different places in the neighbourhood came quickly together, and seemed to vie with one another in the marks of attention and civility which they showed Mr Lunardi,” wrote the Reverend Robert Arnot in The Scots Magazine, describing the Italian’s first landing in a field near Ceres, in Fife.

But the ladies always attracted his attention, as he did theirs. In addition to a measured report of his first Scottish ascent – which “fully gratified the most sanguine expectations of an admiring multitude of all ranks of spectators” – the editor published a poem allegedly written by “young Lady” who promised to follow Lunardi wherever his balloon would take him:

“Shou’d’st thou be plunged below the reach of light,

With thee I’d wander thro’ the realms of night;

Shou’d’st thou glide silent o’er the haunted plain,

With wings of love I’d catch my darling swaine.”

Whether or not she was in the habit of wearing a “Lunardi Bonnet” in his honour, is unknown, but there was, indeed, a brief fashion for wearing a balloon-shaped hat made of gauze and thin muslin stretched on wire, rising some two feet above the wearer’s head. The fashion didn’t last long, but was nevertheless immortalised by Robert Burns in his address To A Louse.

Lunardi would ultimately make six balloon ascents in Scotland: one from Kelso; two from Glasgow’s St Andrews Square; and a further two from the grounds of George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh, one of which ended with him being pulled out of the Firth of Forth.

Sadly, although garlanded with numerous honours – including the freedom of Cupar, St Andrews, Edinburgh and Hawick – Lunardi’s expensive tastes and poor business sense ultimately left him with little money in the bank to show for his Scottish adventures. As the novelty value of balloon ascents quickly began to fade, especially among his richest patrons, Lunardi headed back south, ultimately returning to Italy and his home town of Lucca. Despite a few successful ascents around the Mediterranean, he otherwise endured a nondescript career in the Neapolitan Army. He died in Lisbon, Portugal in 1806.

FOLLOWING IN LUNARDI’S ‘FOOTSTEPS’

Rising gracefully into the sky like Vincenzo Lunardi is easier than you might think, thanks to commercial companies such as Edinburgh-based Alba Ballooning (albaballooning.co.uk) or UK-wide Virgin Balloon Flights (www.virginballoonflights.co.uk). Such companies offer schedules of flights during much of the year, although admittedly not from the city-centre locations Lunardi favoured!

However, while today’s balloons utilise many modern materials and technologies, you’re just as much at the mercy of the weather as Lunardi was 230 years ago! Flights are likely to be confirmed just hours beforehand, and there’s always an element of the unknown; you can never be sure where the wind will take you!

If being a passenger isn’t enough, then you’ll need at least a few thousand pounds to buy a balloon – and even that’s second hand – along with some suitable off-road transport. You’ll also need an appropriate Private Pilot’s Licence (Balloon) issued by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), as a hot air balloon is legally considered a registered aircraft, just like any fixed wing aircraft or helicopter.

If being a passenger isn’t enough, then you’ll need at least a few thousand pounds to buy a balloon – and even that’s second hand – along with some suitable off-road transport. You’ll also need an appropriate Private Pilot’s Licence (Balloon) issued by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), as a hot air balloon is legally considered a registered aircraft, just like any fixed wing aircraft or helicopter.

Most private balloonists in the UK are members of the British Balloon and Airship Club (www.bbac.org); in addition to representing its members in discussions with official bodies such as the CAA, this volunteer-based organisation provides a lot of information on lighter-than-air flight, offers a range of pilot training, and operates a voluntary “sensitive area scheme” marking out areas of farmland which private balloonists should avoid landing in.

First published by The Scots Magazine, November 2015.