The dawn of 1 July 1916 “came with great beauty,” according to Philip Gibbs, a Special Correspondent for The Glasgow Herald and Daily Chronicle, who was “attached with the British Armies in the Field” near the Somme River in France . “There was a pale blue sky flecked with white wisps of cloud,” he wrote. “But it was cold, and over all the fields there was a floating mist which rose up from the moist earth and lay heavily upon the ridge, so that the horizon was obscured.”

Nevertheless, there was plenty of activity along the Allied lines and, at a minute after 7.30am, “there came through the rolling smoke clouds a rumbling sound. It was the noise of rifle fire and machine guns,” Philip Gibbs reported. “The men were out of their trenches, and the attack had begun. The enemy was barraging our lines.”

The Battle of the Somme would roll on until 18 November 1916 – some 141 days later. Later more obviously decisive battles would be fought on the same ground towards the close of the Great War in 1918. A century on, however, 1 July 1916 is still viewed as the blackest day in the history of the British Army, thanks to the estimated 19,200 dead and 40,000 wounded or missing within a single 24 hours period. Most of the casualties fell in the first hundred metres of no man’s land.

There’s little doubt that, during the subsequent century, the Battle of the Somme has come to signify for many the waste and carnage of the First World War, during which thousands of men on both sides died for the smallest territorial gains. As the military historian Andrew Robertshaw points out, in his book Somme 1916: “The Battle of the Somme has become the epitome of the Great War, as it is popularly seen. Futile, muddy, bloody and unnecessary.”

Robertshaw, though, has little sympathy for those who have “a singularly myopic view of the day” and ignore the wider political and military contexts in which the Battle of the Somme should be viewed. Other historians have argued that the Somme was undoubtedly a significant turning point in the conflict; British casualties might have been around 400,000 by November, but the losses on the other side were almost identical. This was fundamentally a terrible battle of attrition that ultimately broke the back of the German army on the Western Front.

There’s little doubt, however, that the Battle of the Somme became a graveyard for many of the Scottish volunteer soldiers who by then were under the ultimate command of the Edinburgh-born General Sir Douglas Haig. Three Scottish divisions – the 9th, 15th (Scottish) and 51st (Highland) – took part in the Battle, as well as numerous Scottish battalions in other units, such as the Scots Guards in the Household Division. All of the 51 Scottish infantry battalions were involved in the 1916 Somme offensive at one time or another, although not always on the front line.

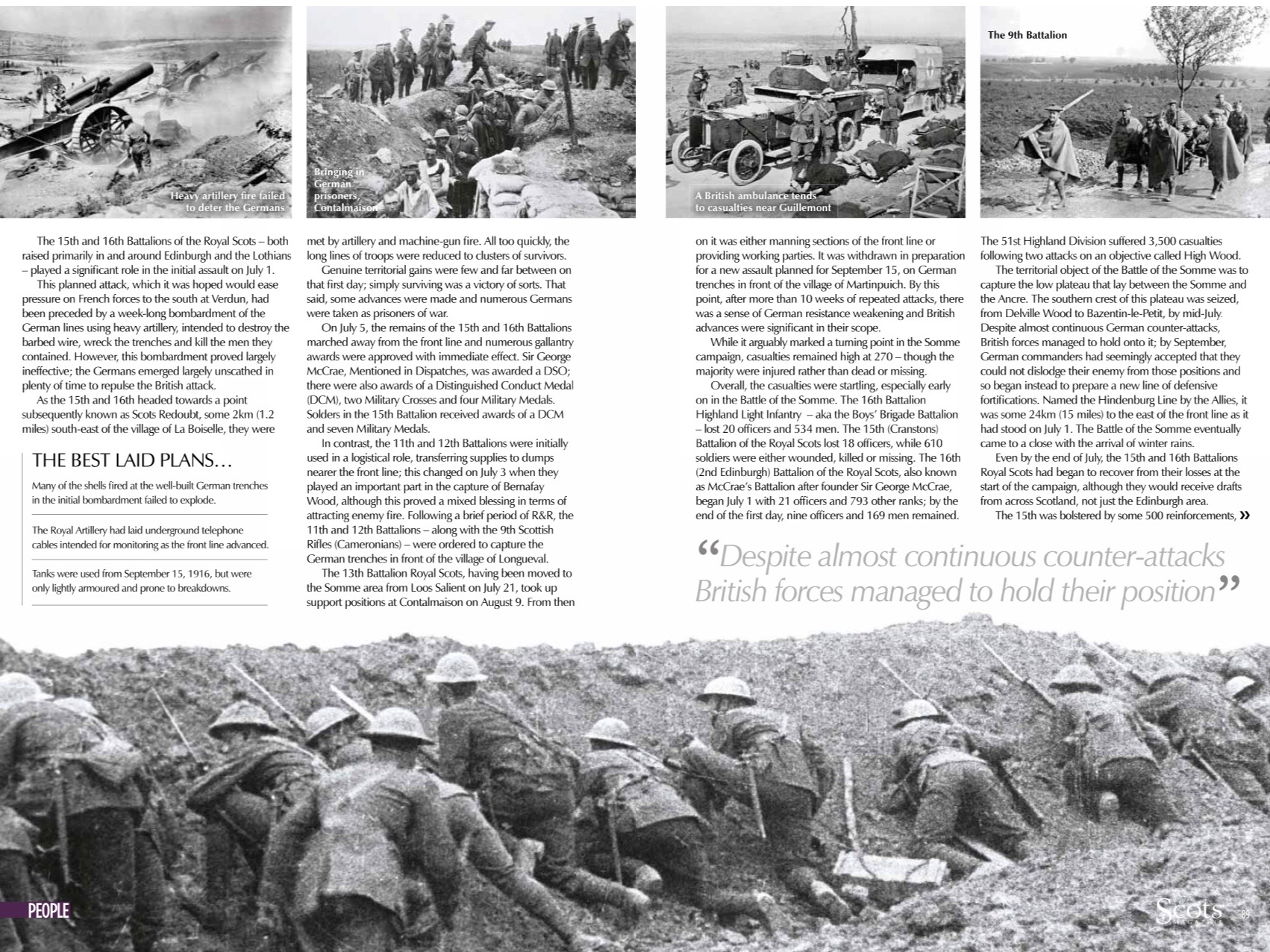

The 15th and 16th Battalions of the Royal Scots – both raised primarily in and around Edinburgh and the Lothians – played a significant role in the initial assault on 1 July. This planned attack, which it was hoped would ease pressure on French forces to the south at Verdun, had been preceded by a week-long bombardment of the German lines using heavy artillery, intended to destroy the barbed wire, wreck the trenches and kill the men they contained. However, this bombardment soon proved to have been largely ineffective; the Germans had been able to shelter within their very strongly built trenches, and emerged largely unscathed in plenty of time to repulse the British attack.

As the 15th and 16th headed towards a point subsequently known as Scots Redoubt, some two kilometres south east of the village of La Boiselle, they were met by enemy artillery and machine-gun fire. All too quickly, the long lines of troops were reduced to clusters of survivors.

Genuine territorial gains were few and far between on that first day; simply surviving was a victory of sorts. That said, some advances were made and numerous Germans were taken as prisoners of war. On 5 July, the remains of the 15th and 16th Battalions marched away from the front line and numerous gallantry awards were approved with immediate effect. Sir George McCrae, Mentioned in Dispatches, was awarded a DSO; there were also awards of a Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM), two Military Crosses and four Military Medals. Solders in the 15th Battalion received awards of a DCM and seven military medals.

In contrast, the 11th and 12 Battalions were initially used in a logistical role, transferring supplies to dumps nearer the front line; this changed on 3 July when they played an important part in the capture of Bernafay Wood, although this proved a mixed blessing in terms of attracting enemy fire. Following a brief period of R&R, the 11th and 12 Battalions – along with the 9th Scottish Rifles (Cameronians) – were ordered to capture the German trenches in front of the village of Longueval.

The 13th Battalion Royal Scots, having been moved to the Somme area from Loos salient on 21 July, took up support positions at Contalmaison on 9 August; from then on it was either manning sections of the front line or providing working parties. It was withdrawn in preparation for a new assault planned for 15 September, on German trenches in front of the village of Martinpuich. By this point, after more than 10 weeks of repeated attacks, there was a sense of German resistance weakening and British advances were significant in their scope. Yet, while it arguably marked a turning point in Somme campaign, casualties remained high – although the majority of the 270 total were injured rather than listed as dead or missing.

Overall, the casualties were startling, especially early on in the Battle of the Somme. The 16th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry (aka the Boys’ Brigade Battalion) lost 20 officers and 534 men. The 15th (Cranstons) Battalion of the Royal Scots lost 18 officers, while 610 soldiers were either wounded, killed or missing. The 16th (2nd Edinburgh) Battalion of the Royal Scots (also known as McCrae’s Battalion after its founder Sir George McCrae), began 1 July with 21 officers and 793 other ranks; by the end of the first day, just nine officers and 169 men remained. The 51st Highland division, meantime, suffered 3,500 casualties following two attacks on an objective called High Wood.

The territorial object of the Battle of the Somme was to capture the low plateau that lay between the Somme and the Ancre. The Southern crest of this plateau was seized, from Delville Wood to Bazentin-le-Petit, by mid-July. Despite almost continuous German counter-attacks, British forces managed to hold onto it; by September, German commanders had seemingly accepted that they could not dislodge their enemy from those positions and so began instead to prepare a new line of defensive fortifications (named the Hindenburg Line by the Allies), some 15 miles to the east of the front line as it had stood on 1 July. The Battle of the Somme eventually came to a close with the arrival of winter rains.

Even by the end of July, however, the 15th and 16th Battalions Royal Scots had began to recover from their losses at the start of the campaign, although a consequence of this was that they would receive drafts from across Scotland, not just Edinburgh and its surroundings. The former was bolstered by some 500 reinforcements, primarily from other Royal Scots Battalions. (This included a draft of nearly 300 men from the former 6th Battalion which, together with the 5th, had been moved to France from Egypt in the Spring of 1916.) The 16th Battalion, meantime, was reinforced with around 370 troops, including 254 from the 5th and 6th Battalions Scottish Rifles (Cameronians).

In general, the conduct of Scottish soldiers had helped confirm their reputation for tenacity and bravery. But, perhaps more significantly, they had played their part in showing how the volunteers in Kitchener’s New Army had successfully integrated with the pre-war Regular Army and the much expanded Territorial forces. It was far from all quiet on the Western front, however; the introduction of conscription later in the year would lead, from 1917, to the creation of a new, more socially and geographically mixed Army.

Admittedly, the bravery and professionalism of those Scottish soldiers wasn’t always appreciated, especially by the locals. Bill Hanlan was one of many Scots who was at the Somme and survived.

“Ah wis in Albert on the Somme,” he told Ian MacDougall, for his book Voices from War, and some Labour Struggles. “Ah remember the Virgin on the church at Albert lyin’ doon. She wis lyin’ towards the German trenches. And the French people reckoned that she was keepin’ the Germans back. They didnae think it was the British that wins haudin’ them back, it wis this Virgin that wis haudin’ them back.”

ONE OF THE MANY WHO FELL

Thousands of Scottish soldiers were injured and killed during the long months of the Somme campaign; George Fisher Cockburn was just one of the many hundreds killed on the first day.

The 29 year old draper from Duns, Berwickshire, had joined – like his younger brother Peter, an apprentice grocer – what was, at the time, arguably the most famous of the new battalions, the 16th (2nd City of Edinburgh) Service Battalion of the Royal Scots, colloquially referred to within the capital as “McCrae’s Battalion”.

Sir George McCrae was a self-made businessman and much respected local politician within Edinburgh. Towards the end of 1914, he had volunteered to raise a battalion – his sole condition to the War Office being that he would be allowed to personally lead it in the field, and therefore share the risks of battle alongside his men. McCrae’s Battalion famously included nearly a dozen players from Heart of Midlothian Football Club, along with hundreds of their supporters.

On the morning of 1 July 1916, while advancing towards the German defences as part of “the great advance in Picardy” (as some British newspapers termed it), George came upon Peter, who had already been injured in the chest. George removed one of his puttees to use as a dressing, before continuing his advance; it’s reported that he turned round just once to shout to his brother: “We’ve got them on the run!”

George was never seen alive again; initially reported as missing, he was later officially confirmed among the dead.

Like many of his peers, George had earlier that year made his Will using standard Army Form B 243; signed on 6 February 1916, he left all his possessions – after “payment of [his] just Debts and Funeral Expenses” – to his mother, Margaret.

Though unmarried, George’s name at least would live on within his family, passed down the generations. His elder brother William, invalided out of the Army after his lungs were badly affected by a German gas attack, later gave his late brother’s name to his only son, born in 1924. That George (Arthur) Fisher Cockburn was my father.

First published in The Scots Magazine, June 2016.