For a small country with an comparatively small population, Scotland’s often been praised for “punching above its weight”, not least when it comes to those inventions — from chloroform anaesthetic to the steam engine and Dolly the Sheep — that have helped shape the future.

For a small country with an comparatively small population, Scotland’s often been praised for “punching above its weight”, not least when it comes to those inventions — from chloroform anaesthetic to the steam engine and Dolly the Sheep — that have helped shape the future.

Yet Scotland has also played a significant role in our understanding of the ancient past. Thanks to its rich and varied geology, Scotland has a fossil heritage encompassing — according to the Scottish Geodiversity Forum — some 1,200 million years of Earth history.

Ancient plants, the world’s oldest known insect, important transitional forms between amphibians and reptiles, and early mammal remains — all have been found preserved in Scotland’s rocks.

Fossil discoveries in Scotland have therefore played an important role in both the science of geology and palaeontology (the study of life before the Holocene Epoch, some 11,200 years ago) — as well as a crucial role in the study of evolution, a scientific theory first proposed by a certain Charles Darwin, a former disaffected medical student at Edinburgh University!

Almost every period of geological time in which life has existed on Earth can be found somewhere in Scotland, according to Nigel Trewin, Emeritus Professor at the University of Aberdeen and author of several books, including Scotland’s Fossils (published by Dunedin Academic Press in 2013).

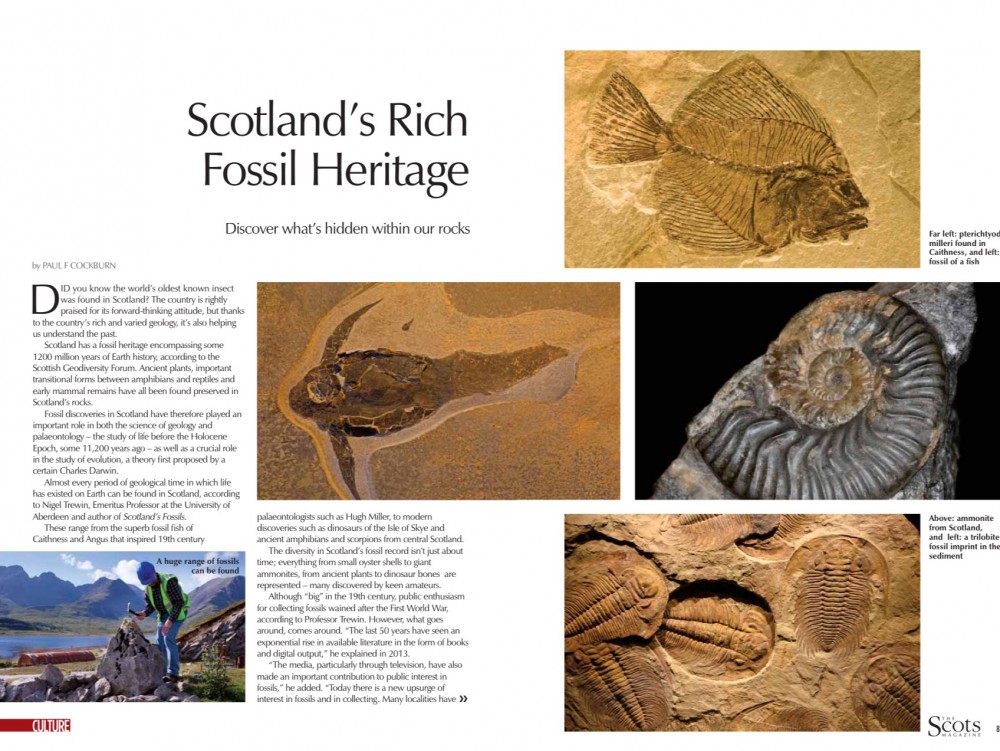

These range from the superb fossil fish of Caithness and Angus that inspired 19th century palaeontologists such as Hugh Miller to modern discoveries such as dinosaurs of the Isle of Skye, and ancient amphibians and scorpions from central Scotland.

The diversity in Scotland’s fossil record isn’t just about time; everything from small oyster shells to giant ammonites, from ancient plants to dinosaur bones, and from primitive armoured fish to superb trilobites, are represented — and many have been discovered by keen, and lucky amateurs with a real interest in the subject.

Although “big” in the 19th century, public enthusiasm for collecting fossils wained after First World War, according to Professor Trewin. However, what goes around, comes around. “The last 50 years have seen an exponential rise in available literature in the form of books and digital output,” he explained in 2013.

“The media, particularly through television, have also made an important contribution to public interest in fossils,” he added. “Today there is a new upsurge of interest in fossils and in collecting. Many localities have hardly been touched for over a century, and there are new finds to be made. It seems we are in a new age of paleontological progress, with enthusiastic amateurs making an increasing contribution.”

However, whether you’re just a tad curious and looking for a different kind of keepsake, or genuinely interested in starting a new hobby, Scotland’s standing in the world of fossils could prove to be a double-edged sword. That’s according to Matt Dale, the owner of Mr Wood’s Fossil Shop just off Edinburgh’s Grassmarket — which has been trading in a wide range of fossils for 25 years.

“Scotland has quite a lot of important fossil sites — localities which have produced lots of fossils which are of globally important significance,” he agrees. “That said, those sites and materials are scarce; it’s very hard to go and find anything that’s not just a scrap of something. To get a kid interested, you’ve got to be able to find something and be able to tell what it is.

“There are some sites in Scotland, where you’ll find something if you spend time, but for instant gratification Scotland doesn’t quite have the same results as maybe the Yorkshire coast or the south coast of England where you can find something pretty quickly. So, whilst there are some significant fossil sites in Scotland, it’s not somewhere that’s going to give you instant rewards.”

Nevertheless, getting started has possibly never been easier than it is today. When Mr Wood’s Fossil Shop first opened — original owner Stan Wood was a former insurance salesman and merchant seaman who “had an eye” for fossils and eventually became highly regarded internationally as a collector — there wasn’t much of a fossil trade in the UK. “There were one or two shops round the coasts in England, where you could find material yourself and fill a shop with your own finds,” says Matt. “To begin with Stan filled the shop with material from one or two suppliers, but it was difficult to get it off the ground. The shop’s since grown alongside the commercial trade.”

Nowadays, there are plenty of good sources of information online, as well as groups and organisations which can link you up with other fossil hunters — or “rock hounds”, as they say in America. “A good place to start is to first of all pick up the Scottish Fossil Code, published by Scottish Natural Heritage,” Matt says. “You can download it from their website, or get a printed version.

“It’s basically a guide to good practice; what you should do, what you shouldn’t, the information you should keep when you find fossils, and how to go about collecting in a responsible way and a manner that won’t disadvantage people who come to the site later. The basics are laid out in a short list, but each point is gone into more detail. You should go into the field with some understanding of what you’re doing. Other than that, it’s just about finding the right spot.”

The legal aspect of fossil hunting varies from country to country, but in Scotland you should have the landowner’s permission to be collecting. Some sites are protected for scientific reasons, but the level of protection varies; again, information on this can be found in the Scottish Fossil Code and elsewhere.

Don’t forget that many of Scotland’s top museums have notable fossil collections; National Museums Scotland, for example, inherited Hugh Miller Collection, some of which remains on loan to the Hugh Miller Museum in Cromarty. The Hunterian Museum in Glasgow, meantime, has one of the largest fossil collections in the UK, built up during the last 200 years from departmental research and teaching collections as well as private donations.

To learn more about collecting, check out the Scottish Fossil Code produced by Scottish Natural Heritage. The Code includes useful information and advice on collecting, preparing specimens and documenting a collection. A digital version can be downloaded: www.snh.gov.uk/docs/B572665.pdf

THE NEWMAN MILLIPEDE!

Back in 2003, Aberdeen bus driver and amateur fossil hunter Mike Newman decided to check out the foreshore of Cowie Harbour, near Stonehaven in Aberdeenshire.

One reason was that the site — well known in fossil collecting circles for its arthropods (animals with segmented bodies and jointed limbs) such as sea scorpions — had been “re-aged”, meaning it was geologically older than previously thought. “Any terrestrial-type things with legs found there could be early and important,” he later told the BBC.

Mike’s discovery of a fossilised one-centimetre millipede certainly proved to be just that. Experts at the National Museums of Scotland and America’s Yale University declared the 428 million years old to be the oldest air-breathing creature so far discovered — by about 20 million years!

Underlining the continuing importance of the amateur in palaeontology, Mike was rather pleased when they named the new species — Pneumodesmus newmani — after him!

First published in The Scots Magazine (April 2015).