The annual Up-Helly-Aa festival, held in Lerwick on the last Tuesday of January, is arguably the most famous and iconic winter celebration in Scotland.

Other communities in Scotland – including elsewhere in Shetland – have winter fire festivals, but arguably none can match the Lerwick Up-helly-aa “for its scale, the vigour of its modern celebration or its significance to the local people,” according to Callum G Brown in his book, Up-helly-aa: Custom, culture and community in Shetland.

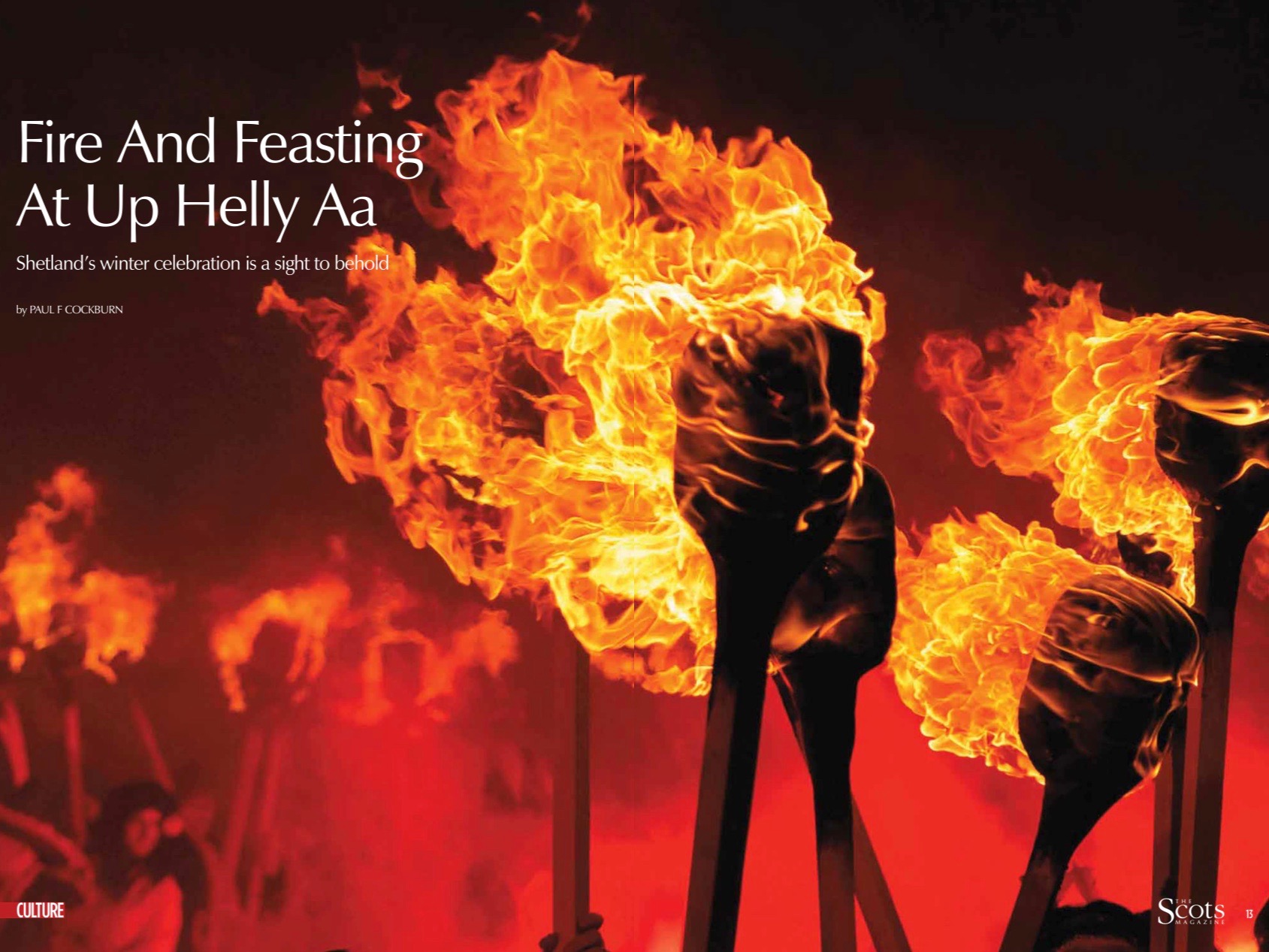

Of course, a night-time parade made up of a thousand men, marching through the streets of the town in lavish masquerade costumes with huge flaming torches, singing praises to medieval Norse heroes as they draw a Viking ship to its ceremonial funeral pyre, is certainly eye-catching.

Of course, a night-time parade made up of a thousand men, marching through the streets of the town in lavish masquerade costumes with huge flaming torches, singing praises to medieval Norse heroes as they draw a Viking ship to its ceremonial funeral pyre, is certainly eye-catching.

Yet there’s much more to the annual celebration than just a photogenic march, and it’s definitely not just something for the tourists – assuming there’ll be that many at a time of year when the islands arguably feel at their remotest.

Visitors are certainly welcome as on-lookers but, as the organisers point out, it’s very much a local event for local people. In order to participate, you must have been a Shetland resident for five years before being able to join one of the many “squads” that make up the main evening procession.

All the organisation and work – from the building of the galley and making of more than 1,000 torches, to the fabrication of individual costumes and masks – is done by local people themselves, funded primarily by local businesses.

For all its sense of “tradition”, however, Up-Helly-Aa is a relatively modern festival: the introduction of the Viking elements, the elaborate element of disguise – guizing – and a torchlight procession all date from the late 1870s. It wasn’t until a decade later that a Viking longship – the “galley” – was introduced, while having a chief guizer – known as “Guizer Jar” – only began in 1906.

Having a squad of Vikings, the “Guizer Jarl Squad”, lead the procession only became a regular feature following the First World War.

Up till the 1940s, the various Up-Helly-Aa festivals around the islands were primarily for young working class men and, for understandable reasons, were often run on a shoestring. Yet that never blunted their sharp satirical edge, or the organisers’ willingness to take an opportunity to “cock a snook” at the local great and the good – Shetland’s own answer to the supposed topsy-turvy world of Twelfth Night.

Certainly the Lerwick celebration begins early, and bitingly, with the erection of a large placard known as “the Bill” at the Market Cross in the centre of the town’s Commercial Street in Lerwick. On this, Guizer Jarl proclaims the calling of Up-Helly-Aa before taking an opportunity to make some near-defamatory remarks about local people, especially councillors. And that’s not the end of it.

Nowadays, Guizer Jarl and his Squad make several parades during the day, visiting local community centres and the Lerwick Royal British Legion, followed by a lunchtime reception at the Town Hall. Their afternoon will involve visits to several local schools, hospitals and eventide homes before concluding at the town’s Shetland Museum.

There is also a separate parade for the town’s school children, with its own junior Guizer Jarl and viking squad.

The main evening parade starts at 7:30pm, and is more or less finished less than 80 minutes later. Its main feature, of course, is fire – lots of it – climaxing with the ceremonial burning of the galley.

However, that’s only the end of the overtly public side of Up-Helly-aa. When the locals turn their backs on the burning boat, they’re not likely to be heading for home. They’re off to party the night away.

Though not in a way you might expect. From around 9pm until 8am, a significant proportion of Lerwick’s inhabitants – along with visitors and expatriates lucky enough to get a ticket – socialise in quite a stylised manner. A dozen locations around the town, including schools and public halls, are designated “the Halls”, where invited guests – mostly women – prepare food and drink for a succession of visits by troupes of the parade’s guizers, who are expected to perform a skit inspired by their outfits. These, again, can be biting and merciless when it comes to the sensitivities of elected officials.

It takes all night for all the squads of guizers to visit each of the the Halls. It’s all, generally, highly respectable, of course; relatively few venues have alcohol on open display, and there are a ready supply of light meals, sandwiches and tea served continuously through the night.

Understandably, not much happens in Lerwick the following day.

Of course, the North Atlantic in darkest winter can be unforgiving, but there’s one certainty you can rely on; when it comes to Up-helly-aa, there’s no postponement on account of bad weather.

“The Viking ship and Norse warriors are icons of island identity, conveying power and machismo, and marking a robust and passionate patriotism for community,” points out Callum G Brown in Up-helly-aa: Custom, culture and community in Shetland.

Significantly, Up-Helly-Aa is very much a man’s event. Yes, there have been rumours down the years that one or two women – on one occasion, reputedly, a journalist – were spirited into the procession, concealed beneath guizing outfits, but it was only in January 2015 that the South Mainland Up-Helly-Aa festival made headlines by appointing 49 year old primary school headteacher and mother of three Lesley Simpson as Guizer Jarl.

As yet there’s no indication that Lerwick will break with tradition in that way. But, given how it has already adapted down the decades, who knows what may happen?

First published in The Scots Magazine, January 2016.