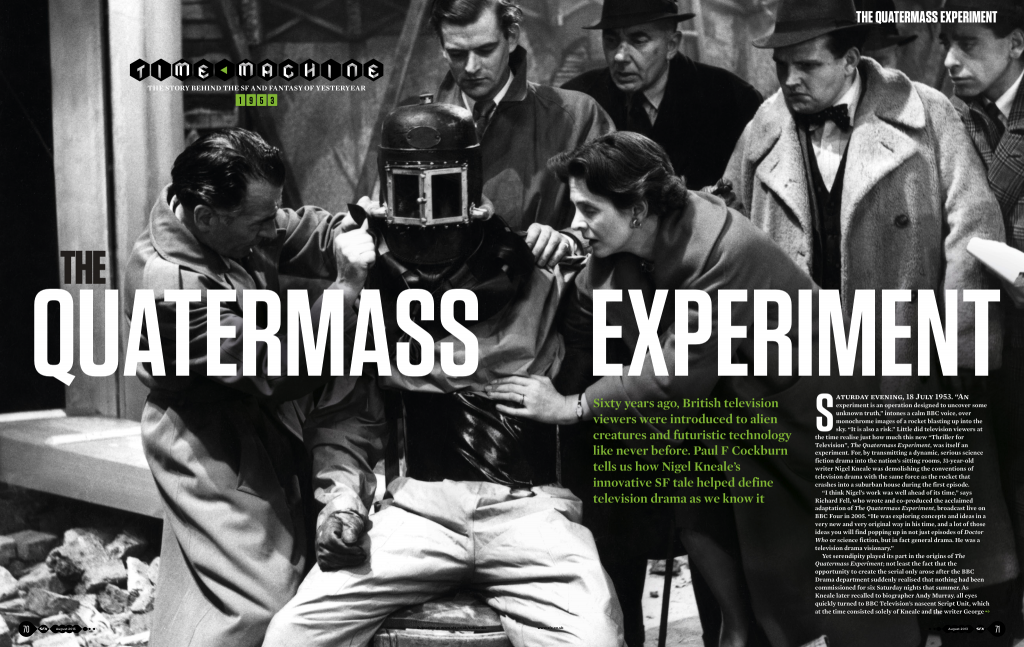

Sixty years ago this month, British television viewers were introduced to alien creatures and futuristic technology like never before. Paul F Cockburn explains how Nigel Kneale’s innovative science fiction story helped define television drama as we know it.

Saturday evening, 18 July 1953. “An experiment is an operation designed to uncover some unknown truth,” intones a calm BBC voice, over monochrome images of a rocket blasting up into the sky. “It is also a risk.” Little did television viewers at the time realise just how much this new “Thriller for Television”, The Quatermass Experiment, was itself an experiment. For, by transmitting a dynamic, serious science fiction drama into the nation’s sitting rooms, the then-31 year old writer Nigel Kneale was demolishing the then-conventions of television drama with the same force as the rocket that crashes into a suburban house during the first episode.

“I think Nigel’s work was well ahead of its time,” says Richard Fell, who wrote and co-produced the acclaimed adaptation of The Quatermass Experiment, broadcast live on BBC Four in 2005. “He was exploring concepts and ideas in a very new and very original way in his time, and a lot of those ideas you will find popping up in not just episodes of Doctor Who or science fiction, but in fact general drama. He was a television drama visionary.”

Yet serendipity played its part in the origins of The Quatermass Experiment; not least the fact that the opportunity to create the serial only arose after the BBC Drama department suddenly realised that nothing had been commissioned for six Saturday nights that summer. As Kneale later recalled to biographer Andy Murray, all eyes quickly turned to BBC Television’s nascent Script Unit, which at the time consisted solely of Kneale and the writer George F Kerr. “They said, ‘For God’s sake write something, because the programme is empty in the summer. Please, somebody think of something.’ So I did.” Not that Kneale had much choice; Kerr was on his summer holidays at the time. “I think they only decided to make it because they were desperate,” Kneale would admit later.

If Kneale’s and Kerr’s holiday plans had been switched, those six empty slots would have been likely filled by competently written adaptations of existing literary or theatrical work; that was, after all, what both writers were contracted to do. Kneale, however, grasped with both hands the opportunity to create a thrilling drama that played to both television’s and his own strengths.

CATHODE RAY EXPERIMENTS

Born in 1922, Thomas Nigel Kneale had arrived at BBC Television a moderately successful prose writer with a penchant for the strange and unnerving, grounded in both his Isle of Man childhood and favourite authors such as H G Wells and M R James. “His short stories had attracted the attention of the publisher Collins,” explains the writer, critic and editor Andrew J Wilson, “who effectively acted as his agent–getting them into magazines and even on BBC Radio–before publishing a collection in 1949. Kneale’s Tomato Cain and Other Stories won the respected Somerset Maugham Award but, although Collins were keen for him to write a novel, Kneale—ever the contrarian—saw the emerging medium of television as a better bet.”

Having accepting that he was unlikely to make a living as either an actor—he had trained at RADA—or short story writer, Kneale badgered the BBC for work and was eventually given one of the earliest staff writing posts at BBC Television. “There were no script editors and, in fact, I was just doing odd jobs,” Kneale told Julian Petley for PrimeTime magazine in 1986. “I did various adaptations and tried to make dramas look less like stagey, drawing room comedies. We even did some work for light entertainment and Children’s Hour.” He was eventually given his first, rolling three-month contract, in 1951.

Although Kneale was generally dismissive of the BBC’s then habit of producing “radio with pictures”, one exception was a 1952 adaptation of Albrecht Goes’ German novel Unruhige Nacht, which had been translated into script form by new BBC producer Rudolph Cartier. “It all sounded a little bit too German, which Rudi was happy to agree with,” explained Kneale. “And so I anglicised it up a bit.” The resulting play, Arrow in the Heart, provided Kneale with not only his first on-screen writing credit (“Additional dialogue”) but also an opportunity to work with a like-minded collaborator. “He was wonderful at pushing the whole project as far as you could possibly go,” said Kneale, “taking terrible risks both with the budget and the very simple technical apparatus available, and making it look as if it was doing more than it really was.”

The two men wouldn’t have the opportunity to work together again until–to Kneale’s delight–Cartier was assigned to produce his “summer filler”, initially titled Bring Something Back, later The Unbegotten, before finally becoming The Quatermass Experiment once Kneale had settled on the name of his hero–“Bernard” after the astronomer Bernard Lovell, then director of the Jodrell Bank observatory, and “Quatermass”, taken from a London telephone directory.

Remarkably quickly, Cartier brought together his cast and crew to work on the serial, even though Kneale was still writing it. “Some of the actors had hardly the sketchiest idea what was supposed to happen,” Kneale admitted later. “The only people who were really in on the secret were Rudi and myself. The others had to take it on trust, which they were good enough to do.” The lack of completed scripts did have one consequence, however–Cartier’s first choice for the lead, André Morrell, turned it down. “He thought it was too much of a risk to his career,” said Kneale, “which was true, particularly as the thing wasn’t finished.” However, Kneale was more than happy with Reginald Tate’s portrayal, even shaping his later scripts to suit the actor’s strengths. Morrell, in turn, would say “Yes” to Quatermass and the Pit six years later.

The first episode, “Contact Has Been Established”, was performed and broadcast as required on Saturday 18 July 1953. “It was received rather sourly when it began—at least by the critics—but by the time it finished, the reaction had changed and they were much more keen on it,” Kneale told biographer Andy Murray. Audience appreciation figures were consistently high and the ratings increased from just over three million to five million, with a significant proportion of viewers staying with the serial from start to finish. As experiments go, Quatermass was judged a success and both Kneale and Cartier were almost immediately rewarded with the task of adapting George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four for broadcast the following spring.

“While it looks pretty crude, you have to remember how much more filmic and fast-paced The Quatermass Experiment was compared to other productions of the time,” says Andrew J Wilson of the first two episodes, the only ones recorded for posterity. “Cartier brings something of German expressionism and its chiasoscuro effects to it. What’s more, the best of the actors–not least Reginald Tate as the pensive and conflicted Quatermass, Isabel Dean as the Professor’s mathematical expert and troubled wife of what’s left of astronaut Victor Caroon, and Paul Whitsun-Jones as the mercurial journalist Fullalove–deliver genuinely nuanced performances. All of that acting gold was a direct product of Kneale’s script.

“The drip-feed of the plot, which is very clear when you read the full script for the series, was, I think, essential to hold an audience in Britain, who were mostly unused to science fiction and hadn’t seen a lot of horror. Ultimately, it delivers a genuinely original SF idea, not something ripped off from the literature, played seriously for adults–both still unusual for TV–and resolves the story by its hero appealing to the intellect and higher emotions, as opposed to the Hollywood solution of pattern bombing the dramatic problem into submission.” This conclusion–rejected by the more action-orienated Hammer film version two years later–was both original and (conveniently) cost-effective.

Arguably, BBC executives of the time never quite understood how to hold on to “talent” such as Kneale, but a few at least recognised the value of what he did, if only in terms of ratings. In 1954, as the BBC faced up to the impending arrival of commercial television in Britain the following year, Controller of Programmes Cecil McGivern wrote in a memo that: “We are going to need many more Quatermass Experiment programmes.”

NIGEL AND BERNARD

“I do have a certain talent for guessing,” the writer modestly said of his career in the BBC’s 2003 Time Shift documentary, The Kneale Tapes. “Writing about people being silly is not interesting, but writing speculation which can go all sorts of ways–good and bad, murderously horrible or just enjoyable–but can be drawn out of what’s going on today… That’s fun.”

For most people, Kneale’s name is now synonymous with Professor Bernard Quatermass, but is that to the detriment of the rest of his career? “So much of Kneale’s work has been lost or is in degraded form, but he wrote the rule book,” insists Andrew J Wilson. “You wouldn’t have Dennis Potter, Alan Bleasdale or Stephen Poliakoff without him. Truthfully, I think people will be watching the Quatermass stories, The Year of the Sex Olympics and The Stone Tape for as long as you can watch images on a screen.”

“Nigel Kneale is remembered from the 1950s not only because he was the first, but that he genuinely understood what the medium of television could do for storytelling,” adds Richard Fell. “The Quatermass Experiment was the first true television drama commissioned with that medium in mind and Nigel was really the godfather to all of television drama in that respect.”

“Sherlock Holmes overshadowed Conan Doyle’s career; that’s what happens when you create an iconic character and put them in compelling situations,” adds Wilson. “Authors may understandably chafe against the fact that they’ve created something larger than themselves, but really, that’s the definition of success! Anyway, The Year of the Sex Olympics goes for £100 on eBay even though you can watch it on YouTube; The Stone Tape has been re-released on DVD, and people I know still talk in hushed terms about Beasts from 1976. That’s not a bad legacy as it stands!”

THE QUATERMASS XPERIMENT

“I hated the film,” Nigel Kneale told biographer Andy Murray, when discussing Hammer’s 1955 adaptation, The Quatermass Xperiment. “They had some quite decent English actors, working their heads off. It just conceivably could have been even worse–but not much.” Kneale’s chief dislike was the casting of fading American actor Brian Donlevy as Quatermass, but it couldn’t have helped that, despite his contracts referencing only adaptations, the BBC insisted it owned all his scripts, sold the film rights over his head and even expected him to brush up the script if required. “I’d assumed, wrongly, that the BBC were gentlemen,” Kneale later said.

ANOTHER EXPERIMENT

“I’ve always been a massive fan of Nigel Kneale and Quatermass,” says the writer and producer Richard Fell, who first suggested to then-BBC Four controller Roly Keating that they attempt a live broadcast of The Quatermass Experiment as part of a season on 50s and 60s television. While the prospect of performing live television excited the cast, led by Jason Flemyng, getting the script right wasn’t without challenges. “We weren’t given six episodes, but I think we held the story together in a coherent way; the rhythms and speed of television drama now are a lot faster than in 1953.”

Originally published in SFX #237.