Edinburgh is a city of bridges, though not all are at all obvious to the eye, as Paul F Cockburn explains.

Edinburgh is a city of bridges, though not all are at all obvious to the eye, as Paul F Cockburn explains.

Bridges, according to art historian and broadcaster Dan Cruickshank, are “incomparable place-makers, man-made landmarks that vie with the memorable works of nature”, playing “key roles in creating and defining the character, nature and aspirations of the city”. Unlike Glasgow or London, Scotland’s capital didn’t grow up around the easiest crossing point of some great river, but the city’s unique geography and the bridges it has inspired nevertheless help define Edinburgh to this very day.

City of Edinburgh Council currently has 532 bridges within its geographical jurisdiction; it owns 306 of these outright, along with the vast majority of the city’s culverts, footbridges and underpasses. The remainder are either privately owned or the responsibility of public bodies such as Scottish Canals, Network Rail and Transport Scotland.

“Edinburgh’s bridges are as much part of its heritage as its monuments, parks and world-famous landmarks,” according to the city’s Transport Convener, Councillor Lesley Hinds. “That these structures have stood the test of time, often serving as busy arterial routes in and out of the centre, is testament to their durability and their importance to life in the capital.

These days an ongoing programme of maintenance work is prioritised by the findings of a rolling schedule of inspections every two years. “Our management of bridges, footbridges and tunnels is essential for keeping the city moving, and as such we have a dedicated team working to ensure their safety and conservation,” Councillor Hinds adds.

Dean Bridge

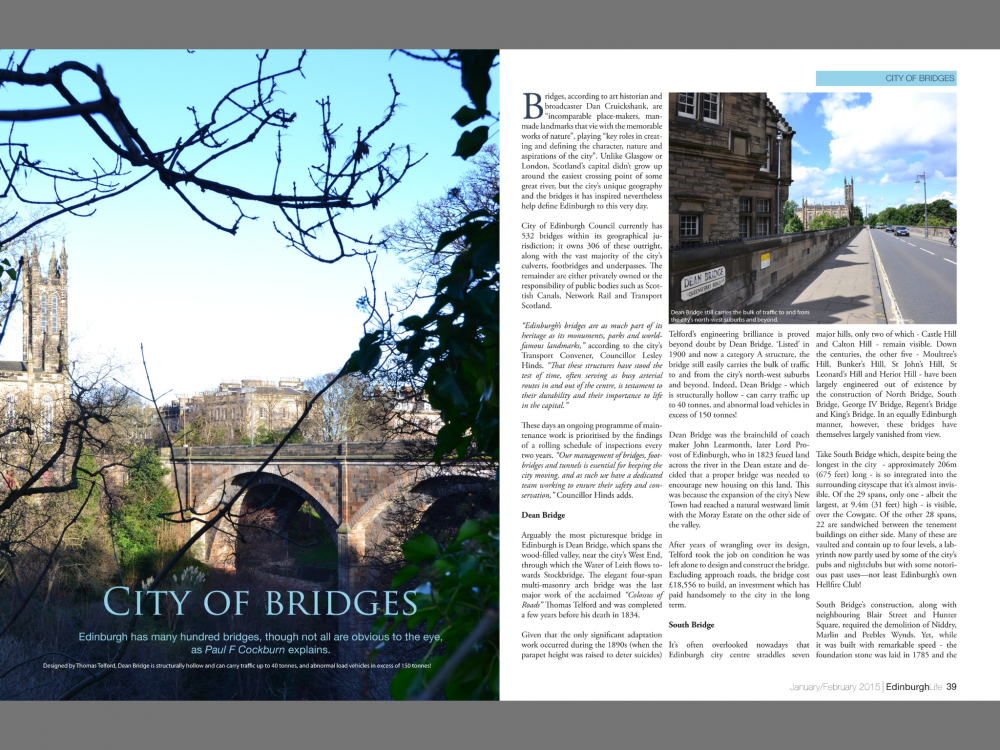

Arguably the most picturesque bridge in Edinburgh is Dean Bridge which spans the wood-filled valley, near the city’s West End, through which the Water of Leith flows towards Stockbridge. The elegant four-span multi-masonry arch bridge was the last major work of the acclaimed “Colossus of Roads” Thomas Telford and was completed a few years before his death in 1834.

Given that the only significant adaptation work occurred during the 1890s (when the parapet height was raised to deter suicides) Telford’s engineering brilliance is proved beyond doubt by the bridge—“listed” in 1900 and now a category A structure—still easily carrying the bulk of traffic to and from the city’s north-west suburbs and beyond. Indeed, Dean Bridge—which is structurally hollow—can carry traffic up to 40 tonnes, and abnormal load vehicles in excess of 150 tonnes!

Dean Bridge was the brainchild of coach maker John Learmonth, later Lord Provost of Edinburgh, who in 1823 feued land across the river in the Dean estate and decided that a proper bridge was needed to encourage new housing on this land—expansion of the city’s New Town having at the time reached a natural westward limit with the Moray Estate on the other side of the valley.

After years of wrangling over its design, Telford took the job on condition he was left alone to design and construct the bridge; excluding approach roads, it cost £18,556, an investment which has paid handsomely to the city in the longterm.

South Bridge

It’s often overlooked nowadays that Edinburgh city centre straddles seven major hills, only two of which—Castle Hill and Calton Hill—remain visible. Down the centuries, the other five—Moultree’s Hill, Bunker’s Hill, St John’s Hill, St Leonard’s Hill and Heriot Hill—have been largely engineered out of existence by the construction of North Bridge, South Bridge, George IV Bridge, Regent’s Bridge and King’s Bridge. In an equally Edinburgh manner, however, these bridges have themselves largely vanished from view.

Take South Bridge which, despite being the longest in the city—approximately 206m (675 feet) long—is so integrated into the surrounding cityscape that it’s almost invisible. Of the 29 spans, only one—albeit the largest, at 9.4m (31 feet) high—is visible over the Cowgate; of the other 28, 22 spans are sandwiched between the tenement buildings on either side. Many of these are vaulted and contain up to four levels, a labyrinth now partly used by some of the city’s pubs and nightclubs but with some notorious past uses—not least Edinburgh’s own Hellfire Club!

South Bridge’s construction, along with neighbouring Blair Street and Hunter Square, required the demolition of Niddry, Marlin and Peebles Wynds. Yet, while it was built with remarkable speed—the foundation stone was laid in 1785 and the bridge opened the following year—South Bridge remains reassuringly sturdy. Indeed, according to the city council’s assessors, it can still safely carry normal traffic up to 40 tonnes and abnormal vehicles in excess of 120 tonnes.

Victoria Hydraulic Bridge

In 1853 both the expansion of Leith Docks (most notably with the opening of the Victoria Dock) and the increased use of railways to serve them required the construction of a new bridge across the Water of Leith that was strong enough to bare the weight of locomotive wagons but still capable of opening to allow ships to berth at quays up to and beyond Bernard Street.

The Docks Commissioners opted for a hydraulic swing bridge designed by A M Rendel of London and built in Darlington and Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Transported by rail early in 1853, the bridge came into use that June, replacing an old manually-operated bridge which was subsequently repaired, altered and relocated over the entrance lock to the Old Docks. Although costing some £30,000, a report written in October 1853 praised the Victoria Hydraulic Bridge’s strength, ease of use and economical maintenance.

After more than a century’s use, the bridge now no longer swings and has been replaced by a permanent bridge carrying Ocean Drive. Pedestrian access is still available along the two walkways on either side of its central timber decked “road”. Comprehensively refurbished by Forth Ports in 1994-5, the bridge remains an iconic local landmark, and recently gained a Category A listing. Its distinctive curved shape has even been reflected in some of the more recent housing built nearby.

Each of these bridges, as well as the hundreds of others across Edinburgh, have contributed to the city’s prosperity—long may they continue to do so!

First published in Edinburgh Life, January/February 2015