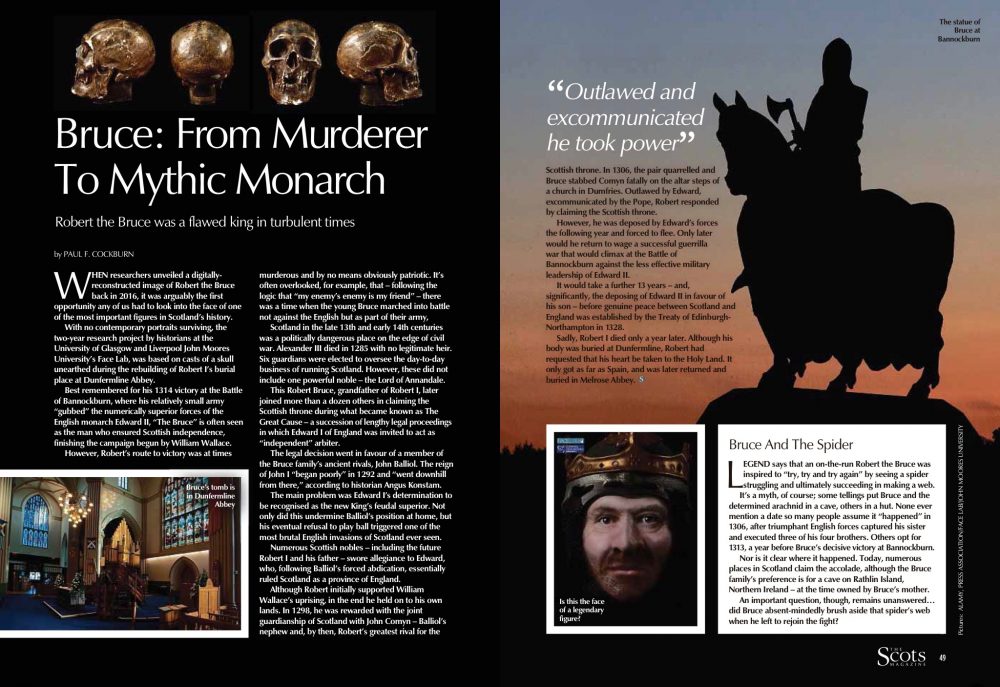

When researchers unveiled, back in 2016, a digitally-reconstructed image of Robert the Bruce it was arguably the first opportunity any of us had to look into the face of one of the most important figure in Scotland’s history.

With no contemporary portraits surviving, the two-year research project – by historians at the University of Glasgow and Liverpool John Moores University’s Face Lab – was based on casts made from a skull unearthed during the rebuilding of Robert I’s burial place at Dunfermline Abbey.

Best remembered for his 1314 victory at the Battle of Bannockburn, where his relatively small army “gubbed” the numerically superior forces of the English monarch Edward II, “the Bruce” is frequently regarded as the man who ensured Scottish independence, finishing the campaign began by William Wallace.

However, Robert’s route to victory was at times murderous and by no means obviously patriotic: it’s often overlooked, for example, that – following the logic that “my enemy’s enemy is my friend” – there was a time when the young Robert Bruce marched into battle not against the English but as part of their army!

Scotland in the late 13th-early 14th centuries was a politically dangerous place, constantly on the edge of civil war: Alexander III had died in 1285 with no legitimate heir. In lieu of any obvious successor, six “guardians” were elected to look after the day-to-day business of running Scotland; however, these did not include one powerful noble, the Lord of Annandale.

This Robert Bruce – grandfather of Robert I – later joined more than a dozen others in claiming the Scottish throne during what became known as “the Great Cause”—a succession of lengthy legal proceedings in which Edward I of England was invited to act as “independent” arbiter.

The final legal decision went in favour of a member of the Bruce family’s ancient rivals, John Balliol, but the reign of John I “began poorly” in 1292, and “went steadily downhill from there,” according to the historian Angus Konstam.

The main problem was Edward I’s determination to be recognised as the new King’s feudal superior; not only did this undermine Balliol’s position at home, but his eventual refusal to “play ball” triggered one of the most brutal English invasions of Scotland ever seen. Numerous Scottish nobles – including the future Robert I and his father – swore allegiance to Edward, who, following Balliol’s forced abdication, essentially ruled Scotland as a province of England.

Although Robert initially supported William Wallace’s uprising, he in the end held onto his own lands and, in 1298, was rewarded the joint guardianship of Scotland with John Comyn—Balliol’s nephew and, by then, Robert’s greatest rival for the Scottish throne.

In 1306, the pair quarrelled; Bruce fatally stabbed Comyn on the alter steps of a church in Dumfries. Outlawed by Edward and excommunicated by the Pope, Robert responded by claiming the Scottish throne. However, he was deposed by Edward’s forces the following year and forced to flee; only later would Robert return to wage a successful guerrilla war that would eventually climax at the Battle of Bannockburn against the less effective military leadership of Edward II.

It would take a further 13 years – and, significantly, the deposing of Edward II in favour of his son – before genuine peace between Scotland and England was finally established by the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328. Sadly, Robert I died only a year later. Although his body was buried at Dunfermline, Robert had requested that his heart be taken to the Holy Land. It only got as far as Spain, and was eventually returned and buried in Melrose Abbey.

BRUCE AND THE SPIDER

Legend says that an on-the-run Robert the Bruce was inspired to “try, try and try again” by seeing a spider struggling – and ultimately succeeding – to make its web.

It’s a myth, of course; some tellings put Bruce and the determined arachnid in a cave, others in a hut. None ever mention a date: so many people assume it “happened” in 1306, after triumphant English forces captured his sister and executed three of his four brothers. Others opt for 1313, just a year before Bruce’s decisive victory at Bannockburn.

Nor is it clear where it happened—it was a hideout, after all! Today, numerous places in Scotland claim the accolade, although the Bruce family’s preference is for a cave on Rathlin Island, Northern Ireland—at the time owned by Bruce’s mother.

An important question, though, remains unanswered; did Bruce absent-mindedly brush aside that spider’s web when he left?

Published by The Scots Magazine, #December 2018.