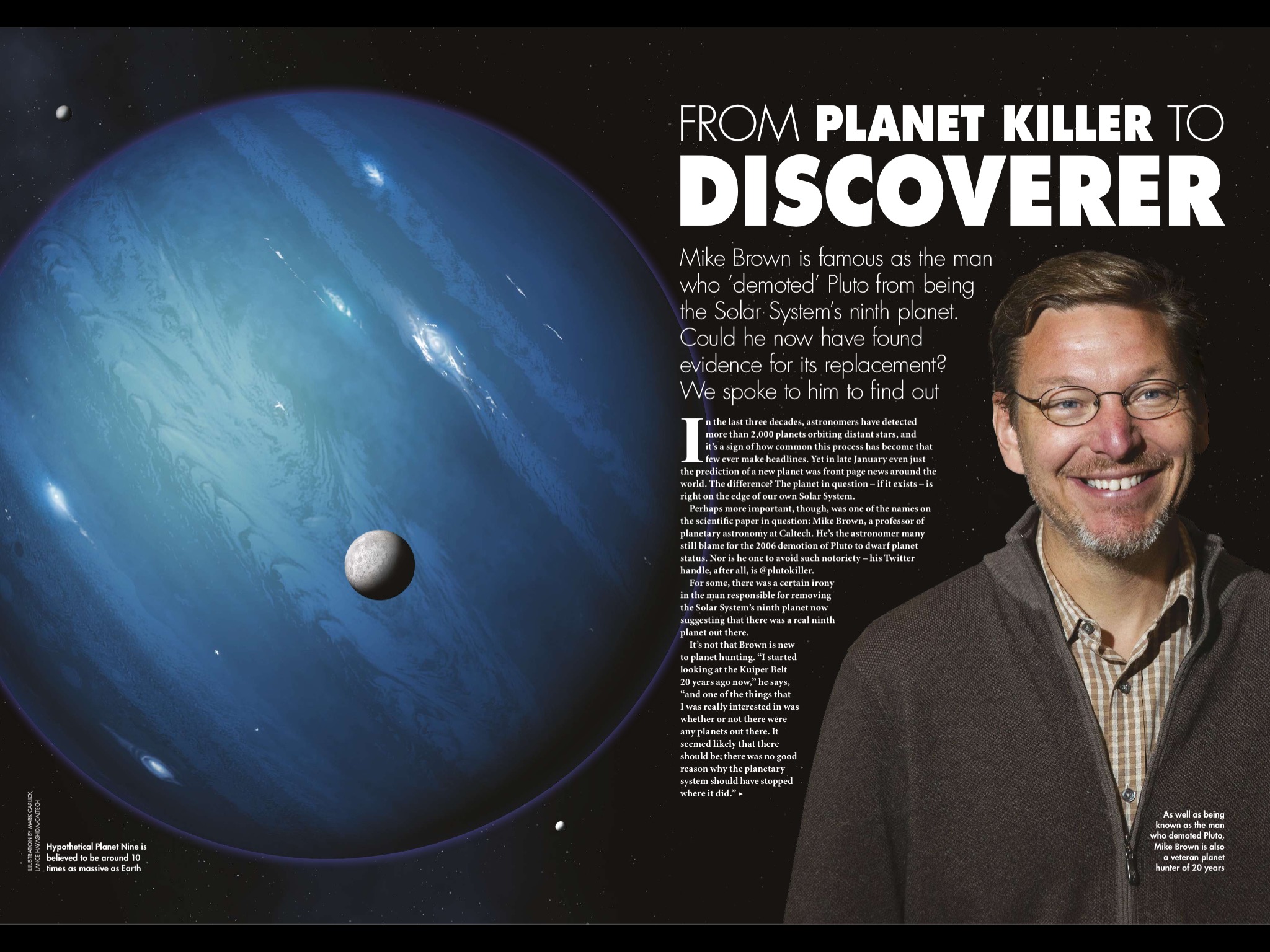

Mike Brown is famous as the man who ‘demoted’ Pluto from being the Solar System’s ninth planet. Could he now have found evidence for its replacement? We spoke to him to find out.

Since 1988, astronomers have detected more than 2,000 planets orbiting distant stars, and it’s a sign of how common this process has become that few ever make headlines. Yet in late January even just the prediction of a “new” planet was front page news around the world. The difference? The planet in question – if it exists – is right on the edge of our own solar system.

Perhaps more important, though, was one of the names on the scientific paper in question: Mike Brown, a Professor of Planetary Astronomy at Caltech (the California Institute of Technology). He’s the astronomer many still blame for the 2006 “demotion” of Pluto to dwarf planet status. Nor is he one to avoid such notoriety – his Twitter handle, after all, is @plutokiller.

Perhaps more important, though, was one of the names on the scientific paper in question: Mike Brown, a Professor of Planetary Astronomy at Caltech (the California Institute of Technology). He’s the astronomer many still blame for the 2006 “demotion” of Pluto to dwarf planet status. Nor is he one to avoid such notoriety – his Twitter handle, after all, is @plutokiller.

For some, there was a certain irony in the man responsible for removing the solar system’s ninth planet now suggesting that there was a real ninth planet out there.

It’s not that Brown is new to planet hunting. “I started looking at the Kuiper Belt 20 years ago now,” he says, “and one of the things that I was really interested in was whether or not there were any planets out there. It seemed likely that there should be; there was no good reason why the planetary system should have stopped where it did.”

Much of Brown’s earliest work was based on big surveys of the outer solar system, which led to two discoveries. Firstly: that there were clearly lots of Pluto-sized objects out there, which controversially led to the reclassification of Pluto. Secondly, there was nothing obviously bigger that could be seen.

Two years ago astronomers Chad Trujillo – a co-discoverer of the dwarf planet Eris – and Scott Sheppard, of the Carnegie Institution for Science, pointed out that the distant minor planet Sedna and several other objects in the Kuiper Belt were acting oddly. “Chad and Scott proposed that maybe there’s a planet out there – because that’s kind of the go-to explanation for any time you don’t understand something in the outer solar system, and has been since 1781.” Brown says. “We looked into it too and realised that their explanation couldn’t be correct, but there were other things going on that they hadn’t seen – that there was a collection of Kuiper Belt Objects that were literally lined up in space together, as if they’re being pulled in one direction.”

Brown brought in his Caltech colleague Dr Konstantin Batygin, whose speciality is the creation of computer models.“He’s three doors down from me, so it was back and forth, back and forth,” he says. “We wore the carpeting out in the hallway between our two offices during this project.” The pair first tried to prove that it couldn’t be a planet. “We looked at every other possible thing that there could be, and we figured out that a planet actually works very well for doing exactly what these objects are doing. Plus it explains a bunch of other things going on that we hadn’t even set out to explain.”

Early on, the pair had dismissed the idea that those particular Kuiper Belt Objects had aligned so perfectly simply by chance. “The probability is something like 0.007%,” he says. Yet that’s still the thing that worries him the most. I’m not worried about the physics. I’m not worried by the N-body simulations. I’m not worried about any of the rest of it. If you have to worry about something, I think you worry about the observations. Sure, we say that the probability is 0.007% but probabilities like that, on data that have been taken by many different people over 15 years, with different telescopes? The numbers are not as straightforward to figure out as I wish they were. I think it’s the right number, but it still keeps me up at night sometimes.”

So when did the “Pluto Killer” begin to believe that there was a real Ninth Planet out there?

“For the first, I would say, 12 months – maybe even 18 months – it was a fun exercise. It was do the maths – yeah, the maths works. Do the simulations – yeah, the simulation work. So a planet was an entirely plausible explanation, though not necessarily a compelling explanation that makes you jump up and down.”

That changed, however, after Brown realised that their simulations predicted that some of the Kuiper Belt Objects gravitationally influenced by this unseen world would have their orbits twisted by 90 degrees, so that they’d basically move perpendicular to the plane of the solar system. When he started looking into more astronomical data, he was surprised to discover there was now an entire series of such objects that people had been slowly finding but not saying much about.

Checking against actual observations, Brown and Batygin found that these perpendicular objects were exactly where their planet-based computer model predicted they would be. “That was the moment where, for me, this was not a cute project any more but: ‘Holy Cow, we just figured out that there’s actually a planet out there.’ And I went from thinking it was plausible to thinking it’s likely that this is really true.”

For Brown it’s clear what has to happen next. “We gotta go find it,” he insists. “On the observational side we are almost finished with the second paper, which will come out very soon; that puts together all of the constraints on where it could possibly be, and also all the old data on all the surveys that might have seen it in the past yet didn’t see it, so we’ll have a pretty good set of constraints on where it could exist. Then we’ll start getting telescopes pointing off in those directions. But at the same time we’re continuing the theoretical work at the computer simulations that we have hope of other ways of trying to pin it down; it’ll help us make the observational quest go even faster too.”

The challenge is that, right now, astronomers only know the plane of the orbit. “That gives us a path through the sky of where the planet should be, but it doesn’t tell us where in its orbit it is – it could be anywhere along a 360 degree swath of that sky. Now we have ruled out a lot of that swath, but we still have a lot that we have to look at.”

Brown’s pretty confident the planet will be directly observed, sooner or later, as – even at its most distant – it will still be bright enough to be detected by the world’s largest telescopes. But how will he feel then?

“When it’s actually discovered, I think that’s the moment where I’ll feel something,” he says. “Right now, I am anxious; I believe it’s there, and I believe it will be found, but there’s a huge gap between believing it and having it actually happen. There’s still this kind of unreality about it; I do believe that at some point somebody is going to point a telescope up at the sky and there it is, but it’s still not quite that moment yet. So I don’t know how that is going to feel until when it actually happens.”

First published in BBC Sky at Night magazine, #131, April 2016.